Humans in Europe Might’ve Taken Toolmaking Inspiration From Neanderthals

Table Of Content

There’s more than one way to make a stone tool. That’s according to a new analysis of artifacts from Lebanon and Italy, which determined that modern humans manufactured their tools in distinct ways in the Near East and Europe around 42,000 years ago.

Revealing their results in the Journal of Human Evolution, the study authors say that these different approaches arose independently, with one theoretically taking inspiration from the Neanderthals, challenging the traditional theory that migrating humans imported the toolmaking traditions of the Near East to Europe as they moved.

“Our study adds to a growing body of research portraying modern human expansion into Eurasia as a complex, non-linear process” said Armando Falcucci, a study author and an anthropologist from the University of Tübingen, according to a press release. “It underscores the importance of recognizing the often-underestimated scope of cultural interactions with our extinct relatives when reconstructing our species’ deep past.”

Read More: Neanderthals Roamed Across Eurasia Before Modern Humans

Toolmaking on the Move

Map of the Mediterranean showing the geographic locations of the analyzed sites and the reconstructed sea level approximately 42,000 years ago.

(Image Credit: Armando Falcucci)

Of course, it’s traditionally thought that modern humans took their technological traditions along with them when they traveled to new territories. In fact, it’s a common theory that the stone tool culture of modern humans in the Near East was introduced to Europe when they migrated from one to the other around 60,000 years ago.

In accordance with this theory, it’s often assumed that the Ahmarian toolmaking tradition from the Levant inspired the Protoaurignacian tradition from Europe, around 42,000 years ago.

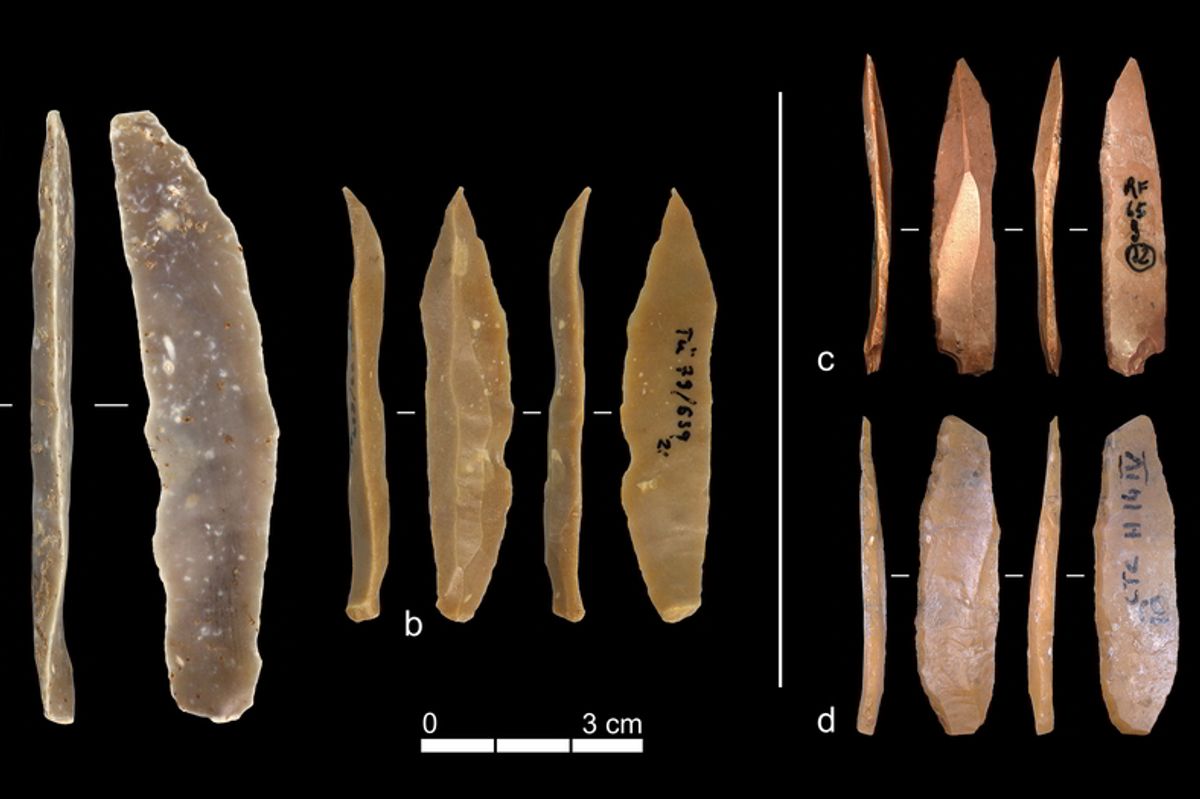

Though the two cultures are seemingly similar, their resemblance and archaeological relationship haven’t historically received much quantitative attention from researchers. To address this, Falcucci and a colleague turned to stone tools from four archaeological sites in Lebanon and Italy, systematically studying thousands of artifacts from Ksar Akil in Beirut, Riparo Bombrini in Ventimiglia, Grotta di Fumane in Verona, and Grotta di Castelcivita in Salerno.

“Superficially, the stone tools from these different areas may look similar,” said Steven Kuhn, another study author and an anthropologist from the University of Arizona, according to the press release. “But we wanted to look deeper, examining in detail how they were produced.”

Read More: Humans and Neanderthals Interbred in Northern Europe Over 45,000 Years Ago

Near East and European Tools

Concentrating on the stone components from composite tools, or tools that feature two or more materials, Falcucci and Kuhn detected differences in Ahmarian and Protoaurignacian manufacturing. While toolmakers in the Near East and Europe both made smaller and smaller blades, for instance, their methods differed, suggesting that the Ahmarian tradition wasn’t the original source of the Protoaurignacian one.

“Overall, the techniques of the Ahmarian and post-Ahmarian cultures in the Near East do not match those of the Protoaurignacian culture,” Falcucci said in the press release. “The differences in flaking methods suggest that European hunter-gatherers developed their projectile technologies independently.”

Read More: DNA Analysis Reveals 7,000 Years of Human-Neanderthal Relations

Taking Tips From Neanderthals?

So, if the Ahmarian didn’t inspire the Protoaurignacian, what did? According to Falcucci and Kuhn, one possible option is that the Châtelperronian culture, a toolmaking tradition that’s commonly associated with the Neanderthals, influenced the Protoaurignacian culture. Indeed, they theorize that modern humans met with Neanderthals when they moved from the Near East to Europe, exchanging technological techniques as well as genes in their encounters.

While future work will be required to test whether Neanderthals influenced the Protoaurignacian tradition, Falcucci and Kuhn stress that their study shows that the evolution of human technology was much more complicated than previously thought, involving more surprises, and possibly more species, than typically expected.

“The common assumption that all Paleolithic technological innovations in Europe were introduced through successive waves of migration from the Near East needs to be re-evaluated,” Kuhn said in the press release. Whether that reassessment will involve the Neanderthals, well, that’s something for the next analysis to reveal.

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: