Ancient Human Brains Adapted From Exposure to Lead Poisoning, Providing an Evolutionary Advantage

Table Of Content

Lead poisoning has plagued millions of people ever since the world became industrialized, but humans’ troubled relationship with the toxic metal goes back much further in time. Our ancient ancestors also had to deal with lead as they breathed in volcanic ash and drank contaminated water.

A new study published in Science Advances has revealed that humans have been exposed to lead for over two million years. The proof lies in fossilized teeth that carry marks of lead uptake, indicating that the metal has been in our systems since long before the Industrial Revolution.

The Dangers of Lead Poisoning

In the modern age, lead is rightfully maligned as a critical danger to public health. The metal is not necessary to have in our bodies, and when it builds up, it can cause a range of health issues like high blood pressure, nerve disorders, abdominal pain, and fatigue. High levels of lead can induce significant brain damage, sometimes resulting in death.

Lead poisoning is a particular area of concern for children, since they absorb more lead than adults do. Children who are exposed to excessive amounts of lead will often show signs of developmental and cognitive issues as they grow.

Lead is naturally occurring in the Earth’s crust, but the real danger is in sources of lead that come from industrial activities like mining and smelting. Lead contamination in consumer products is another potential source of exposure. Harmful levels of lead have recently been found in certain brands of protein powder and cinnamon, for example.

Read More: Lead Poisoning Is Still a Major Problem — Here’s How it Impacts Our Health

A Long History of Lead Exposure

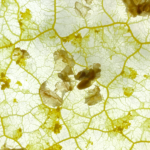

The new study proves that ancient humans were also exposed to lead, albeit in exclusively natural ways. Upon examining 51 fossil teeth from hominid and great ape species, researchers found signs of episodic lead exposure in 73 percent of the specimens.

They came to this conclusion after identifying lead bands in the teeth, which suggest that lead entered the specimens’ bodies through environmental sources like contaminated water, soil, or volcanic activity. Lead that had built up in their bones from these sources could’ve also later been released into the body by stress or illness.

“Our data show that lead exposure wasn’t just a product of the Industrial Revolution — it was part of our evolutionary landscape,” said author Renaud Joannes-Boyau, a professor at Southern Cross University, in a statement. “This means that the brains of our ancestors developed under the influence of a potent toxic metal, which may have shaped their social behavior and cognitive abilities over millennia.”

Building Resistance to Brain Damage

To understand the effects of lead on the brain, the researchers turned to miniature, lab-grown brain models. They focused on two versions of a developmental gene called NOVA1: one that represented a modern human variant and another that represented an archaic variant found in extinct hominids.

When the archaic NOVA1 variant was exposed to lead, brain activity in regions associated with speech and language development was significantly disrupted. The same level of lead exposure in the modern NOVA1 variant, on the other hand, showed a lesser negative effect in those regions. This suggests that at some point, humans gained improved protection against the neurological effects of lead with the modern NOVA1 gene variant.

The researchers say that this genetic adaptation to tolerate lead better than other hominids may have even shaped the development of human language and group-level social cohesion, giving us an evolutionary advantage over Neanderthals and other hominids.

“Our work not only rewrites the history of lead exposure,” said Joannes-Boyau, “it also reminds us that the interaction between our genes and the environment has been shaping our species for millions of years, and continues to do so.”

Read More: What Research Says About the Lead-Crime Hypothesis

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: